The Sadness of Her Sewing

There she remains,

In the folds of her nightgown

Tucked deeply in her bedside drawer,

Releasing the scent of her Chantilly.

And here, in her treasured clip-on earrings

Of aurora borealis rhinestones,

All the colors of the northern lights,

She explained.

And perhaps most,

Up there on the closet shelf,

Her well-worn sewing basket,

A frayed tapestry on its lid of

A young woman’s gentle face.

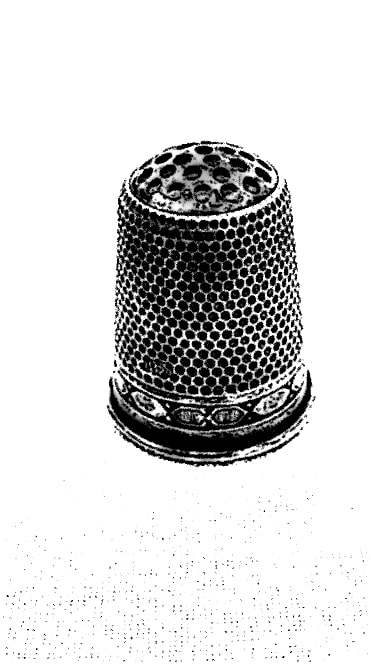

There, inside, among the bobbins of thread,

Mother’s tarnished metal thimble,

Its tiny nubs worn smooth from use.

Remembering how whenever she mended,

I would hear her sigh deeply

As the thimble’s cap clicked

Against her flying needle,

Her impatience palpable,

So desperate was she to be done.

Knowing now it reminded her of

Being pulled from school at the age of nine,

Pressed into piecework for a gruff Glasgow furrier,

Stitching together heavy coats in dingy rooms

From piles of animal pelts,

Never to return to school,

Or childhood,

Again.

~~ Tricia McCallum

Thanks for sharing