Funeral Sandwiches

It comes down to the ceremony now, the detail.

Pressing your shirt with the cutaway collar, not too much starch,

the way you liked it.

I chose the shoes that were a bit small,

but they were so fine-looking and you would approve.

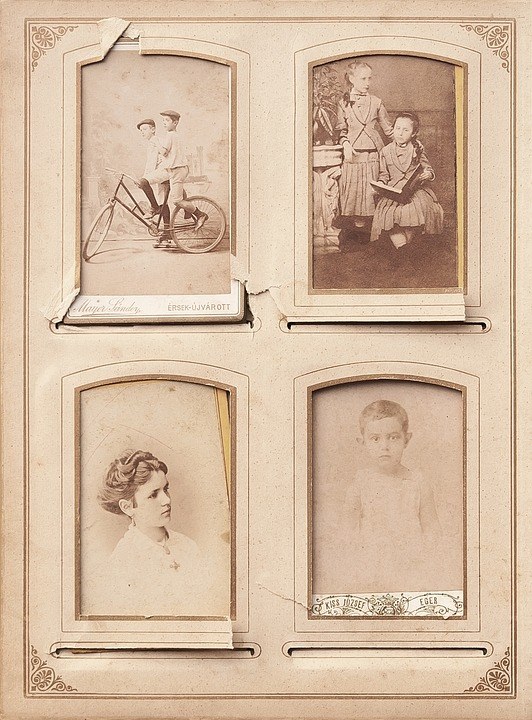

At the last minute I remembered your favourite photo of all of us

for tucking into your suit jacket pocket.

Now to prepare the food for the mourners,

sandwiches to begin.

Made differently today,

the correct word is painstakingly.

The butter spread

to each and every corner of the bread,

sliced precisely

from freshly-baked loaves.

Heap both sides of the bread lavishly with spreads,

no scrimping.

No celery, you hated it.

Remove the crusts.

Assemble them ever so gently

before making the final cuts

into perfect quarters.

wiping the knife clean

after each cut.

Display them proudly

on the most treasured serving pieces.

Delicate china tea cups and matching saucers,

and cloth napkins alongside.

Only cloth.

All is ready.

Invite them in.

I’ll get this right

for all the times

I didn’t.

~~ Tricia McCallum

Thanks for sharing