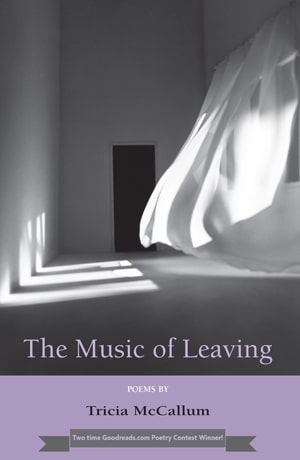

Something Called Qi

My friend made an appointment

with the city’s much acclaimed doctor of Eastern medicine,

way down on the Danforth above the Roots store.

He opened the session by counselling her vehemently

via his earnest translator

to keep the nape of her neck covered at all times

in order to guard against the marauders,

the incoming toxins.

She hadn’t even removed her coat.

This guy meant business.

First he asked her to stick out her tongue,

a diagnostic tool esteemed among Eastern prognosticators,

the sight of which prompted from him a harangue in Mandarin.

It seemed her tongue was seemingly the wrong color and texture,

not to mention tone,

this a sure-fire flag to her malaise,

something called her Qi entirely out of whack,

but you pronounce it chi.

The ancient art of cupping came next.

She followed orders, open to all of it ,

this woman who once scoffed at yoga, calling upon the ancients now,

flipping onto her back wordlessly, bare from the waist up.

The click and then the hiss of the Bic lighter

as the small discs of thick clear glass were heated,

then placed on her back in turn,

one replacing another in swift succession.

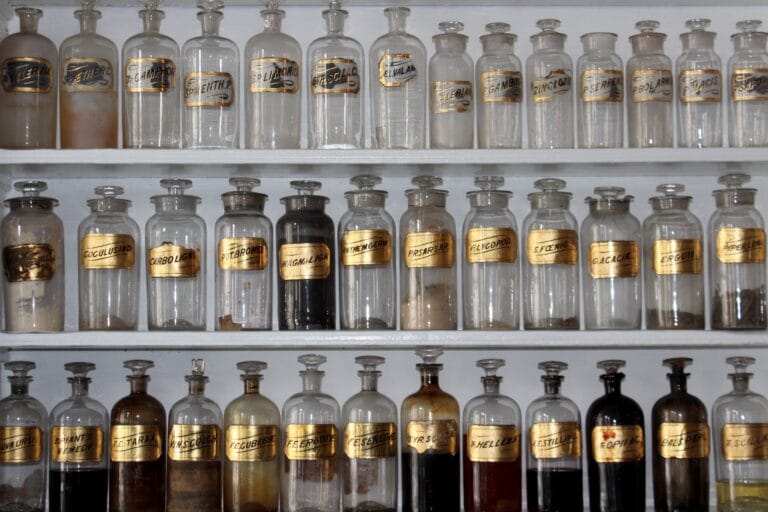

A lengthy script for a herbal concoction came next,

to be purchased in Chinatown,

Mondays and Wednesdays only.

And call first.

I used to think chemo was bad,

she joked to the doctor at their next session,

confessing she could not choke down

even one more drop of his prescribed brew,

its smell alone prompting memories of a dismal sheep farm

we had worked on together years ago in New Zealand.

The doctor’s final words were succinct:

No pepper, no spice, no hot, he admonished,

It takes time.

Time, he counselled, his hand upon hers,

clarifying for my friend what in the end

no one in the East nor the West

was able to give her.

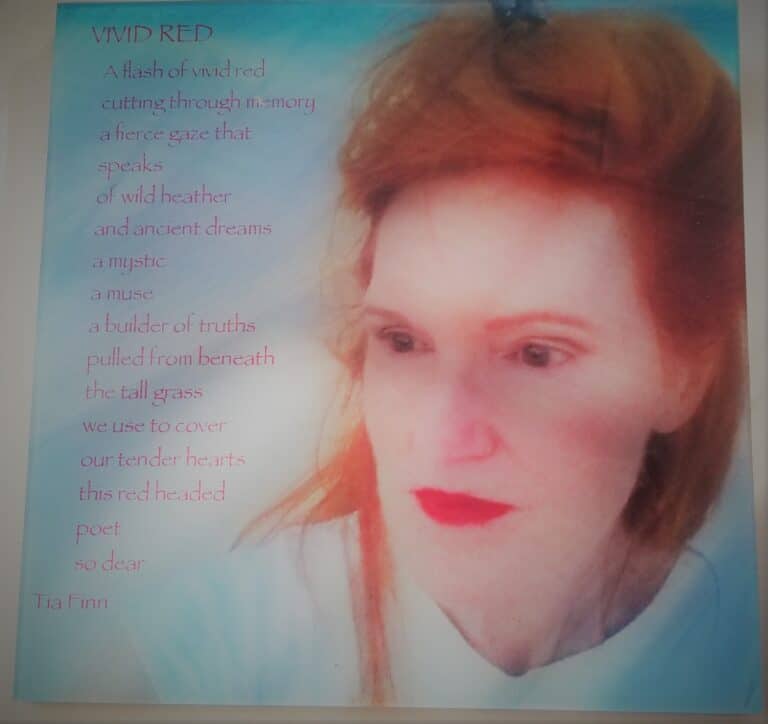

Thanks for sharing